You can look at your nutrition, your pills, teas, massage, cryotherapy and the type of compression you wear, but when it comes to recovery for better performance, sleep is the best tool you have. It’s free, it takes little effort, and we feel like doing it every day (“I forgot to sleep,” said no-one ever). So why do we get it so wrong?

Sleep and the athlete

You have a day off when your muscles are sore, but your brain never rests until you sleep. This is when the brain gets to catch up on its role in the recovery and rebuilding of the body by regulating important hormones such as growth hormone, which is released to the body especially during deep (slow wave or Stage 4) sleep.

Sleep is when the brain does most of its production of the energy-producing chemical ATP (adenosine triphosphate), which is needed for protein synthesis and powering muscle contractions. It’s also the time when you update your athletic skills and technique to your brain, because it’s the time when you consolidate what you’ve learned. It’s also when your brain reinforces emotional memories. So that means that if your hill sprint session hurt like hell for 25 minutes, but then you had five minutes of feel-good sensations, your brain might reinforce those positive feelings during sleep. This tricks you into developing good training habits.

Quantity vs quality

Sleep researchers tend to agree that adults need about seven to nine hours sleep each day. If you’re in heavy training, you might benefit from more. In his book, Running with the Kenyans, Adharanand Finn said the Kenyans sleep up to 14 hours a day while training. In the USA, Cheri Mah at Stanford University conducted several studies of swimmers and basketball players, finding that extra sleep had a significant positive impact on their speed and performance.

Research has only very recently honed in on what a cluster bomb prolonged lack of sleep can be for your health. A landmark study at University of Chicago showed that just six consecutive days of four hours sleep raised blood pressure and levels of the stress hormone cortisol, halved the usual number of antibodies to a flu vaccine and brought on signs of insulin resistance, the precursor of type 2 diabetes and metabolic slowdown (e.g. getting fatter on less calories). All these changes were reversed when the lost snooze was caught up.

If you’re slammed for sleep (new baby, anyone?), then is there a point where a lack of sleep is sets you up for injury?

“Six hours is kind of a cut-off,” says Dr Ian Dunican from Sleep4Performance, which has worked with the AIS, Western Force and other elite athletes.

“Cognitive performance decline can lead to slips, trips and falls, mistiming, and miscalculations that can lead to injury,” Dunican says.

“Plus if you’re not getting enough non-REM sleep for recovery overnight, then you’re just going to be breaking your body down over time.”

Embrace your chronotype. It might mean shifting things around so that you can train late afternoon or evening instead of early morning before work or extending your lunch hour a couple times a week. The quality and consistency of your training will benefit.

Not all time in bed is the same. Sleep scientists talk about sleep efficiency, which is the percentage of time in bed actually spent asleep – so the time you spend in bed reading, lying with eyes shut waiting for sleep to come, and all the times you wake up during the night are deducted. ‘Normal’ sleep efficiency is about 85%, while 90% or more is the ideal.

“The problem is that self-reported quality sleep is basically crap,” Dunican says. In his work, he finds athletes’ estimations of their sleep times are out by as much as 90 minutes.

The gold standard for sleep measurements is polysomnography, which is when someone is completely wired up in the laboratory. Dunican’s world-first research shows that after this the next best measures come from validated wrist-worn devices that use a tri-axial accelerometer to measure movement, such as a Readiband™. These can occasionally overestimate your sleep time because it’s hard to differentiate lying quietly in bed from lying in bed asleep, but they still have an accuracy rate of 92% compared to polysomnography. After this come non-validated wrist-activity monitors that measure heart rate and heart rate variability, such as Fitbit and Garmins – but forget those phone apps.

“Sleep cycle apps are crap,” Dunican warns.

If you lie awake a lot before or after you first fall asleep, or you just feel like you have rubbish sleep, you might have a sleep disorder.

Dunican says that people often think sleep disorder are only for people who are older, fat and smokers or drinkers, but his research has shown that athletes just as likely and sometimes more likely to have one of the 80 different sleep disorders compared to the general population.

There are many disorders that even a partner in the same room wouldn’t be aware of, including disorders where the brain doesn’t send a signal to breathe, and a REM disorder where you feel that you can’t move.

“We find that nearly one in three athletes have some kind of sleep disorder that needs to be managed,” Dunican says.

What’s your time?

If you always feel like crap on a stick at early morning training sessions, then maybe it’s just not your time of day.

“The biggest issue I’ve seen with athletes and coaches is a lack of understanding of chronotype,” Dunican says.

“Chronotype basically means, are you more suited to getting up early in the morning and going to bed early, or are you better suited to going to bed late and getting up late.

If you want to get the most out of your training and have better motivation to turn up for training in the first type, then embrace your chronotype. It might mean shifting things around so that you can train late afternoon or evening instead of early morning before work or extending your lunch hour a couple times a week. The quality and consistency of your training will benefit.

However, if you’re training for an event that will be at a time of day you don’t usually train, then you need to make an adjustment.

“Professional boxers and MMA fighters do this well,” Dunican says. “They’ll do their sparring in the evening around the time that they have their scheduled bout, even if that’s at 11pm, so they get used to operating at that time.”

This brings up another problem. Exercise improves the quality of sleep, but it can disrupt sleep if it’s done too close to bed time – but this depends on the activity. The higher the level of mental stimulation and contact, the harder it will be to unwind enough to sleep. So while slow steady-state run or swim on your own allows you to tune out and sleep soon afterwards, at the other extreme you have guys playing a Super Rugby match that finishes at 10pm.

“There is no point trying to sleep for at least four hours after a night game,” Dunican says.

“People shouldn’t stress about the time they fall asleep after a game or competition. They should be more worried about is creating the opportunity to catch up on sleep and recover the next day and even the following day.”

Too hyped for sleep

Overstimulation is the enemy of sleep, and Dunican says the usual suspects are caffeine and other stimulants such as pre-workout mixes.

“If you have a cup of coffee, it’s going to take about an hour to peak, then about four hours to leave your system.”

Alcohol is another culprit. Alcohol is a depressant, so it can help you fall asleep, but then it all goes downhill after that because it leads to fragmented sleep.

“About two hours after falling asleep, you’ll start waking up due to the alcohol metabolising in your system and trying to be eliminated,” Dunican says.

“You’ll start waking up to urinate, and although your brain could experience arousals – you might not be aware of it, but we would see these in a laboratory with electrodes placed on your head.”

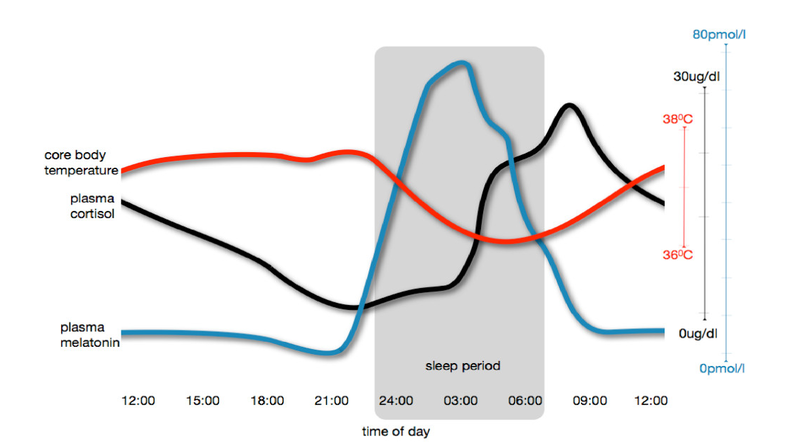

Several other external influences mess with the brain when it tries to wind down for sleep. Here’s what happens. You have two hormones that have an inverse relationship when it comes to sleep. Cortisol helps keep you stimulated during the day, then starts easing up in the evening, which is when melatonin levels begin to rise in the body to prepare you for sleep. Combative-type behaviour or reactions in the evening wreck this balance – the cortisol levels shoots up, which holds back the melatonin secretion. So if you’ve been sparring, getting into some aggro on a night out, hit Rambo mode on social media or played violent video games, don’t expect to sleep well in the next few hours. Got a fight brewing with your partner? Dunican suggests saving that hot mess until mid-morning. (Break-up brunch, anyone?)

“Have a good night’s sleep, some caffeine, then from 9am to midday you’re in that zone of good cognitive performance and you’re not going to make any rash decisions.”

Sleep remedies

Synthetic forms of GABA (gamma-Aminobutyric acid) and melatonin are often pushed as the magic bullet for sleep, but both have flaws.

GABA is a chemical made in the brain to blocks impulses between nerve cells, but in February the University of California School of Public Health reported that “there’s no credible evidence that taking GABA orally increases its levels in the brain”.

Melatonin is a hormone whose main job is to regulate when you sleep and when you are awake.

“People take over-the-counter melatonin for sleep, but a lot of studies show that melatonin doesn’t really help,” Dunican says.

“It’s more of a placebo effect – its greatest effect is in regard to jet lag.”

Melatonin is restricted as a prescription drug in Australia (but not in the USA). You can find so-called melatonin and GABA products on shelves in shops, but they are limited to a miniscule 6X homeopathic strength melatonin, which is unlikely to have any effect at all.

“Two supplements I do recommend to athletes are magnesium and zinc,” Dunican says.

“The studies are a little bit variable, but some show that they can increase the quantity of deep sleep or slow-wave sleep, which is when growth hormone is released.

“One of the challenges as men get older is that we tend to have less deep sleep, so anything we can do to increase that, the better it will be for keeping up testosterone levels.”

Dunican says that especially when training in the heat, magnesium and zinc can help relieve periodic limb movement disorder or ‘restless legs’ while you’re trying to sleep.

“I recommend powdered magnesium because it absorbs better in the gut and gets into the system quicker.”

The urge to move the legs can also be connected to low iron levels, and Dunican says that if iron is on the low side, a liquid iron supplement may help make you a little calmer before sleep and relax the legs.

In Australia, “natural” over-the-counter sleep formulas often contain herbal ingredients such as passion flower, chamomile and valerian. While these have a long history of traditional use for anxiety and sleep, they have very little scientific evidence to support them. Some studies have indicated small benefit from herbal teas, but researchers suggested that the ritual of chilling with a warm tea – almost regardless of its ingredients – was relaxing and reinforced a pre-sleep routine.

This is one thing sleep researchers agree on – the importance of a pre-sleep routine to signal to the brain that it’s time to go into sleep mode. Reducing physical and mental stimulation in the hours before bed is crucial, and pre-bed stretching or yoga can help relieve tension and stiffness in the muscles to bring on better sleep sooner. Light is another important factor. Dim the lights a couple hours before bed – even if you read before sleeping, use a lamp that makes a gentle haze, not a search-and-rescue spotlight. Make a habit of reading something relaxing on paper or listening to a podcast for up to 20 minutes. You work on good habits and routine for training and diet – now it’s time to pay that some respect to your sleep.

This article first appeared in Men’s Fitness magazine.